Building My First Website, Pt. 2

Table of Contents

Intro

My last post ended with me tearing down the website I had built in S3. I’ll briefly go over the architecture, the two revisions I made, and the reasons why I just up and abandoned S3 static website hosting altogether.

CloudFront + S3 + Exposed Buckets

You can launch a working website extremely quickly with AWS. All you need is an index.html file and a 404/error.html file and you’ve got yourself a landing page and you guessed it, a page where you can serve when your users try to access a non-existent page on your site. The problem with this set-up is that due to AWS permissions, the bucket, your “folder” if you will, is fully exposed to the public.

Your bucket needs to be publicly available because users need to have access to the HTML, images, and other files to be served your website via a browser. As long as you don’t keep any sensitive information there, you can leave it, but it’s absolutely not recommended. I could have stopped here as well, but what’s the point of writing this blog and learning if I’m going to half-ass everything?

That is why I decided to incorporate CloudFront, a CDN. For those of you who don’t know, you can think of it as a product that goes in front of your website, caches the content of your S3 bucket, and serves it to users around the world, with the added benefit of keeping your data in various data servers around the world so it can be served quicker. Once I set that up, I thought I was done. I could finally make my buckets private while still serving up my site. All I needed was to enable OAC (Origin Access Control), which restricts communication between the buckets and the CDN so as not to expose them.

Much to my dismay, it turns out that tutorials as of five months ago are now simply outdated. There is no OAC option available when you are using static website hosting. I tried for a long time to get this to work, to find workarounds, to see what I was doing wrong until I found a relevant AWS doc with a handy little snippet: “If your origin is an Amazon S3 bucket configured as a website endpoint, you must set it up with CloudFront as a custom origin. That means you can’t use OAC (or OAI). OAC doesn’t support origin redirect by using Lambda@Edge.” (Source: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonCloudFront/latest/DeveloperGuide/private-content-restricting-access-to-s3.html). So this means I really can’t keep my buckets private, but this only applies to my configuration, arguably the most popular method to host a website in AWS.

As I read more, I found out there is a way to keep nearly the same architecture, with the exception of static website hosting having to be turned off. This involves setting up an additional service called CloudFront Functions, little snippets of code that will help redirect you to the correct page in your website. To clarify, this private-bucket method means you can’t simply type in your browser adriancreates.dev/hello and expect that to return the webpage. The way it works is that internally CloudFront doesn’t see it as a webpage but as a folder hierarchy; the “www.adriancreates.dev” part of the URL is treated more or less like a parent folder followed by a “hello” object. CloudFront is looking for a folder followed by an object that’s supposed to be named “hello,” but as it doesn’t find anything like that, it errors out and presents a 404 page. This is where CloudFront Functions come in. The code you set up takes that URL and rearranges it, sends it back to CloudFront in a way it can understand, and voilà, you now can access the specific subpage you had typed into the browser.

Yeah, I don’t like that. It feels very hacky and “Frankenstein-like.” There may be some irony in this in that my goal is to learn more AWS, but this particular solution that involves relatively few moving parts is all of a sudden “too much.” This really feels like a very abnormal way to set up a website. Hence, when I attempted this solution, I re-read the banner AWS displays about recommending Amplify instead, and right then and there I decided to delete everything and use it instead. I wasn’t sure what it was really or how to configure it, but it beats whatever the above is.

AWS Amplify or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Hugo.

What is Amplify? It’s basically a mobile and web app hosting service. It integrates with GitHub and can update your website and/or app as soon as you update your GitHub repository that’s linked to it. It’s also inexpensive, and you pay (as of now) one cent per minute of “build” time. Upon finding this out, I was immediately ecstatic. This was serendipitous and exactly what I wanted—more CI/CD and more Git. We were actually going to do some DevOps-like work!

Now that I had a domain and my hosting option set up, I got to work on connecting my GitHub profile to Amplify, installing Git, and setting up my “dev” environment. I had to relearn how to commit changes and push code into a repository and get my head around .git files again, but it’s all part of the process.

I won’t talk in depth about why I chose Hugo as my static site generator, as the answer is mostly because I remembered a former co-worker’s personal site was built with it. After briefly learning about it, it checked everything I wanted. It was lightweight, popular, and had hosting instructions for Amplify. For those of you who don’t know what a static website generator is, it takes a pre-packaged theme and necessary files to generate a production-ready website. You can paste the code into any repository, and Amplify and other services can build the website or simply run it locally on your machine to see changes before you publish it.

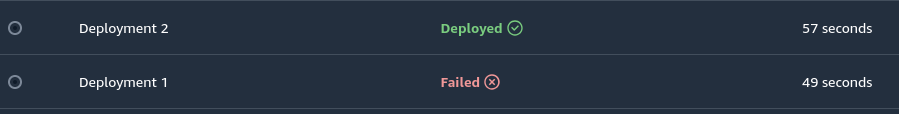

Countless hours later, I had the hang of Hugo, how it works, what .toml files are, and after following the official documentation, pushed my code out to my repo. Of course it failed the first time. Nice.

Deployment failure lol

This was due to the YAML file that Hugo uses to send instructions to Amplify on how to build the webpage. In that file, I had essentially told Amplify to go into a folder that did not exist, and when it couldn’t find the relevant files to build, it failed. I had to go back in and edit the file to read cd ActualWebsiteFolder. Super simple fix. Once it was able to traverse into that folder, it built everything, and I finally had a production-ready website—the very same one you’re reading!

What’s Next?

There it is, folks. Hopefully, you learned something, were entertained, or took some enjoyment from getting into someone’s head as they navigated the multitude of ways of getting a website up and running. As to what’s next — I plan on writing about my experience this year switching from Windows to Linux by way of Fedora, more projects I take on, and perhaps an unrelated piece or two. Maybe I’ll set up that About page next.